Basic concepts of speech recognition

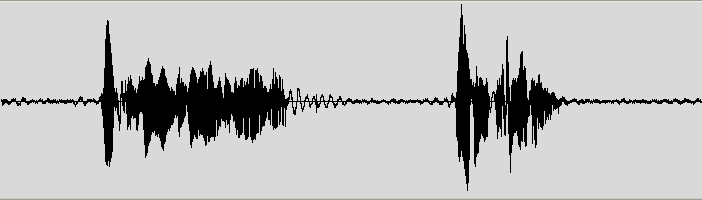

Speech is a complex phenomenon. People rarely understand how it is produced and perceived. The naive perception is often that speech is built with words and each word consists of phones. The reality is unfortunately very different. Speech is a dynamic process without clearly distinguished parts. It’s always useful to get a sound editor and look into the recording of the speech and listen to it. Here is, for example, the speech recording in an audio editor.

All modern descriptions of speech are to some degree probabilistic. That means that there are no certain boundaries between units, or between words. Speech to text translation and other applications of speech are never 100% correct. That idea is rather unusual for software developers, who usually work with deterministic systems. And it creates a lot of issues specific only to speech technology.

Structure Of Speech

In current practice, speech structure is understood as follows:

Speech is a continuous audio stream where rather stable states mix with dynamically changed states. In this sequence of states, one can define more or less similar classes of sounds, or phones. Words are understood to be built of phones, but this is certainly not true. The acoustic properties of a waveform corresponding to a phone can vary greatly depending on many factors - phone context, speaker, style of speech and so on. The so-called coarticulation makes phones sound very different from their “canonical” representations. Next, since transitions between words are more informative than stable regions, developers often talk about diphones - parts of phones between two consecutive phones. Sometimes developers talk about subphonetic units - different substates of a phone. Often three or more regions of a different nature can be found.

The number three can easily be explained: The first part of the phone depends on its preceding phone; the middle part is stable, and the next part depends on the subsequent phone. That’s why there are often three states in a phone selected for speech recognition.

Sometimes phones are considered in context. Such phones in context are called triphones or even quinphones. For example, “u” with left phone “b” and right phone “d” in the word “bad” sounds a bit different than the same phone “u” with left phone “b” and right phone “n” in the word “ban”. Please note that unlike diphones, they are matched with the same range in waveform as just phones. They just differ by name because they describe slightly different sounds.

For computational purposes it is helpful to detect parts of triphones instead of triphones as a whole, for example if you want to create a detector for the beginning of a triphone and share it across many triphones. The whole variety of sound detectors can be represented by a small amount of distinct short sound detectors. Usually we use 4000 distinct short sound detectors to compose detectors for triphones. We call those detectors senones. A senone’s dependence on context can be more complex than just the left and right context. It can be a rather complex function defined by a decision tree, or in some other ways.

Next, phones build subword units, like syllables. Sometimes, syllables are defined as “reduction-stable entities”. For instance, when speech becomes fast, phones often change, but syllables remain the same. Also, syllables are related to an intonational contour. There are other ways to build subwords - morphologically-based (in morphology-rich languages) or phonetically-based. Subwords are often used in open vocabulary speech recognition.

Subwords form words. Words are important in speech recognition because they restrict combinations of phones significantly. If there are 40 phones and an average word has 7 phones, there must be 40^7 words. Luckily, even people with a rich vocabulary rarely use more then 20k words in practice, which makes recognition way more feasible.

Words and other non-linguistic sounds, which we call fillers (breath, um, uh, cough), form utterances. They are separate chunks of audio between pauses. They don’t necessarily match sentences, which are more semantic concepts.

On top of this, there are dialog acts like turns, but they go beyond the purpose of this document.

Recognition Process

The common way to recognize speech is the following: we take a waveform, split it at utterances by silences, and then try to recognize what’s being said in each utterance. To do that, we want to take all possible combinations of words and try to match them with the audio. We choose the best matching combination.

There are some important concepts in this matching process. First of all, it’s the concept of features. Since the number of parameters is large, we are trying to optimize it. Numbers that are calculated from speech, usually by dividing the speech into frames. Then for each frame, typically of 10 milliseconds in length, we extract 39 numbers that represent the speech. That’s called a feature vector. The way to generate the number of parameters is a subject of active investigation, but in a simple case it’s a derivative from the spectrum.

Second, it’s the concept of the model. A model describes some mathematical object that gathers common attributes of the spoken word. In practice, for an audio model of senone, it is the gaussian mixture of it’s three states - to put it simply, it’s the most probable feature vector. From the concept of the model, the following issues arise:

- how well does the model describe reality,

- can the model be made better, given its internal model problems and

- how adaptive is the model if conditions change

The model of speech is called Hidden Markov Model or HMM. It’s a generic model that describes a black-box communication channel. In this model process is described as a sequence of states which change each other with a certain probability. This model is intended to describe any sequential process like speech. HMMs have been proven to be really practical for speech decoding.

Third, it’s a matching process itself. Since it would take longer than universe existed to compare all feature vectors with all models, the search is often optimized by applying many tricks. At any point we maintain the best matching variants, and extend them as time goes on, producing the best matching variants for the next frame.

Models

According to the speech structure, three models are used in speech recognition to do the match:

An acoustic model contains acoustic properties for each senone. There are context-independent models that contain properties (the most probable feature vectors for each phone) and context-dependent ones (built from senones with context).

A phonetic dictionary contains a mapping from words to phones. This mapping is not very effective. For example, only two to three pronunciation variants are noted in it. However, it’s practical enough most of the time. The dictionary is not the only method for mapping words to phones. You could also use some complex functions learned with a machine learning algorithm.

A language model is used to restrict word search. It defines which word could follow previously recognized words (remember that matching is a sequential process) and helps to significantly restrict the matching process by stripping words that are not probable. The most common language models are n-gram language models; these contain statistics of word sequences–and finite state language models; these define speech sequences via finite state automation, sometimes with weights. To reach a good accuracy rate, your language model must be very successful in search space restriction. This means it should be very good at predicting the next word. A language model usually restricts the vocabulary that is considered to the words it contains. That’s an issue for name recognition. To deal with this, a language model can contain smaller chunks like subwords or even phones. Please note that the search space restriction in this case is usually worse and the corresponding recognition accuracies are lower than with a word-based language model.

Those three entities are combined together in an engine to recognize speech. If you are going to apply your engine for some other language, you need to get such structures in place. For many languages there are acoustic models, phonetic dictionaries, and even large vocabulary language models available for download.

Other Concepts Used

A Lattice is a directed graph that represents variants of the recognition. Often, getting the best match is not practical. In that case, lattices are good intermediate formats to represent the recognition result.

N-best lists of variants are like lattices, though their representations are not as dense as the lattice ones.

Word confusion networks (sausages) are lattices where the strict order of nodes is taken from lattice edges.

Speech database - a set of typical recordings from the task database. If we develop a dialog system, it might be dialogs recorded from users. For dictation systems it might be reading recordings. Speech databases are used to train, tune and test decoding systems.

Text databases - sample texts collected for e.g. language model training. Usually, databases of texts are collected in sample text form. The issue with such a collection is to put present documents (like PDFs, web pages, scans) into a spoken text form. That is, you need to remove tags and headings, to expand numbers to their spoken form, and to expand abbreviations.

What Is Optimized

When speech recognition is being developed, the most complex problem is to make search precise (consider as many variants to match as possible) and to make it fast enough to not run for ages. Since models aren’t perfect, another challenge is to make the model match the speech.

Usually the system is tested on a test database that is meant to represent the target task correctly.

The following characteristics are used:

Word error rate: Let’s assume we have an original text and a recognition text with a length of N words. I is the number of inserted words. D is the number of deleted words, and S represents the number of substituted words. With this, the word error rate can be calculated as

WER = (I + D + S) / N

The WER is usually measured in percent.

Accuracy: It is almost the same as the word error rate, but it doesn’t take insertions into account.

Accuracy = (N - D - S) / N

For most tasks, accuracy is a worse measure than the WER, since insertions are also important in the final results. However, for some tasks, the accuracy is a reasonable measure of the decoder’s performance.

Speed: Suppose an audio file has a recording time (RT) of 2 hours and the decoding took 6 hours. Then the speed is counted as 3xRT.

ROC Curves: When we talk about detection tasks, there are false alarms and hits/misses. To illustrate these, ROC curves are used. Such a curve is a diagram that describes the number of false alarms versus the number of hits. It tries to find the optimal point where the number of false alarms is small and the number of hits matches 100%.

There are other properties that aren’t often taken into account, but are still important for many practical applications. Your first task should be to build such a measure and systematically apply it during system development. Your second task is to collect the test database and test how your application performs.